Water crisis: Experts call for tackling the water-energy-food-ecosystem nexus

The World Water Day brought the spotlight on the global water crisis

image for illustrative purpose

Often, water is plentiful but is too polluted to be useful for drinking, manufacturing or recreation. Measuring water quality can help policymakers prioritize actions to clean up water sources. This evaluation can be complemented by satellite data, artificial intelligence and even citizen science

Today, 2.4 billion people live in water-stressed countries, defined as nations that withdraw 25 per cent or more of their renewable freshwater resources to meet water demand.

Hard hit regions include Southern and Central Asia, and North Africa, where the situation is declared critical. Even countries with highly developed infrastructure, like the United States, are seeing water levels drop to record lows.

Along with climate change, the crisis is being fed by unchecked urbanization, rapid population growth, pollution and land development. Water shortfalls already affect everything from food security to biodiversity and in the coming years. They are poised to become more common.

By 2025, 1.8 billion people are likely to face what the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) calls “absolute water scarcity” and two-thirds of the global population is expected to be grappling with water stress.

They are all symptoms of a world facing what experts call a water crisis. At least 50 per cent of the planet’s population – four billion people – deals with water shortfalls, at least one month of the year.

The World Water Day on March 22 brought the spotlight on the global water crisis, which is being driven by a combination of factors, from climate change to leaky pipes.

Ahead of that international observance, here is a look at seven things countries and individuals can do to stem water shortfalls.

The ecosystems that supply humanity with fresh water are disappearing at an alarming rate. Wetlands, peat lands, forested catchment areas, lakes, rivers and groundwater aquifers are falling victim to climate change, overexploitation and pollution. This is undermining their ability to provide communities with water. These natural spaces urgently need to be protected and those that have been degraded, revived through large-scale restoration.

Countries would be well served to develop specific, measurable targets for this work. Nations should ideally weave those goals into national plans to counter climate change, protect biodiversity and avoid drought and desertification. This work is especially important for securing water supplies for cities, many of which are suffering from acute shortages.

Agriculture accounts for some 70 per cent of all fresh water used globally. Adopting water-saving food production methods, such as hydroponics, drip irrigation and agroforestry, can help water reserves stretch further. Also helpful: encouraging people to switch to plant-based diets, which generally require less water than those based around meat.

Being efficient also means reducing the amount of water lost through leaky municipal infrastructure and building piping. There is no global data for the amount of water lost this way but numbers suggest the total is massive. In the United States of America alone, household leaks waste nearly one trillion gallons of water per year.

As supplies of lake, river and aquifer water dwindle, countries will need to get creative. This means taking advantage of undervalued water resources, such as by treating and reusing wastewater. Countries and communities can also implement rainwater harvesting, which involves collecting and storing water for use in dry spells. Desalinating saltwater is also an option in some places if done sustainably. The problem: the process often leads to the discharge of toxic brine into the ocean and increased greenhouse gas emissions from the energy required to fuel the process.

Often, water is plentiful but is too polluted to be useful for drinking, manufacturing or recreation. Measuring water quality can help policymakers prioritize actions to clean up water sources. This evaluation can be complemented by satellite data, artificial intelligence and even citizen science. UNEP’s Freshwater Ecosystems Explorer provides decision-makers with water quality data, helping to spur action to protect and restore freshwater ecosystems.

Climate change is affecting rainfall patterns, aquatic habitats and the availability of good quality water. At the same time, peat-lands and other watery carbon warehouses are being degraded, causing planet-warming emissions to spike and compounding climate change. To manage this destructive feedback loop, countries must emphasize the protection and restoration of carbon sinks. They should also harmonize their strategies for managing water with their policies for limiting and adapting to climate change.

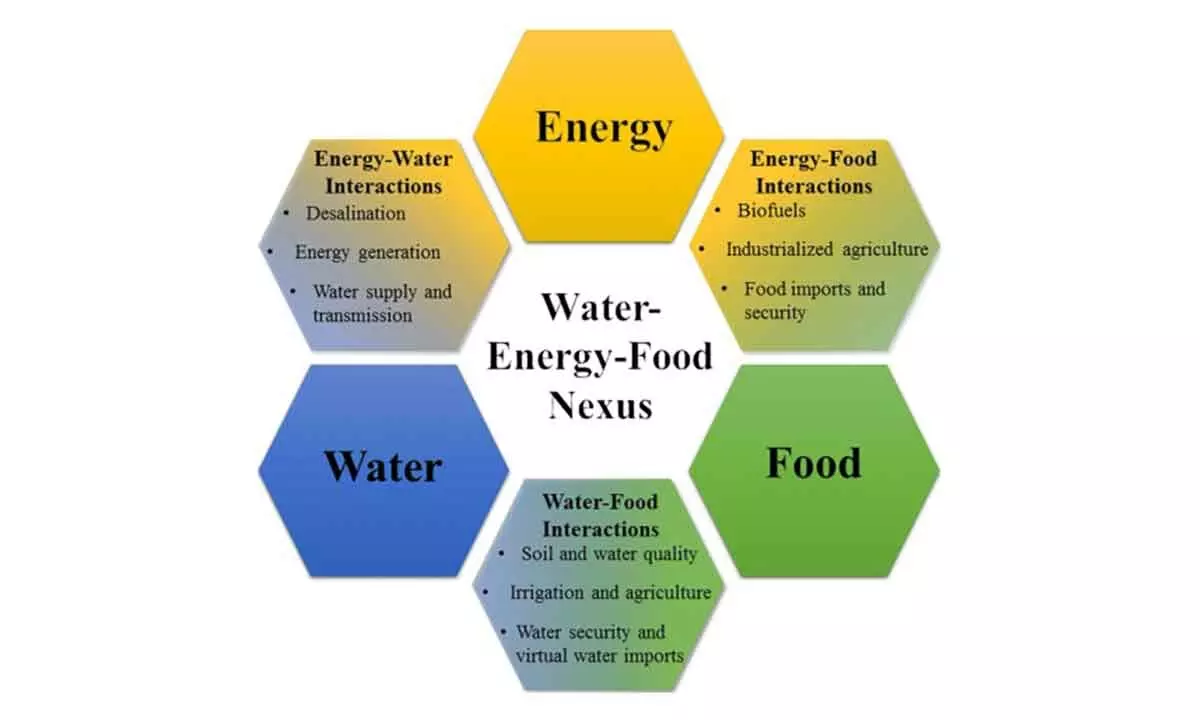

Decisions about water cannot be made in a vacuum. Water is a key component in everything from power generation to industrial manufacturing to farming.

So, countries must develop action plans that address water use and pollution across multiple sectors, tackling what experts call the water-energy-food-ecosystems nexus. This approach can help countries adopt coherent responses to water-related challenges while maximizing food production and energy generation.