Recognise 60+ people as agents of societal development and act accordingly

By 2050, two-thirds of the 60+ population will be from low and middle-income countries

image for illustrative purpose

Public health professionals, and society as a whole, need to address these and other ageist attitudes, which can lead to discrimination. Globalization, technological developments, urbanization, migration and changing gender norms are influencing the lives of older people. A public health response must take stock of these current and the projected trends and frame policies accordingly

Most people worldwide are living longer and well beyond their sixties. Every country is experiencing growth in both size and proportion of older persons in the population.

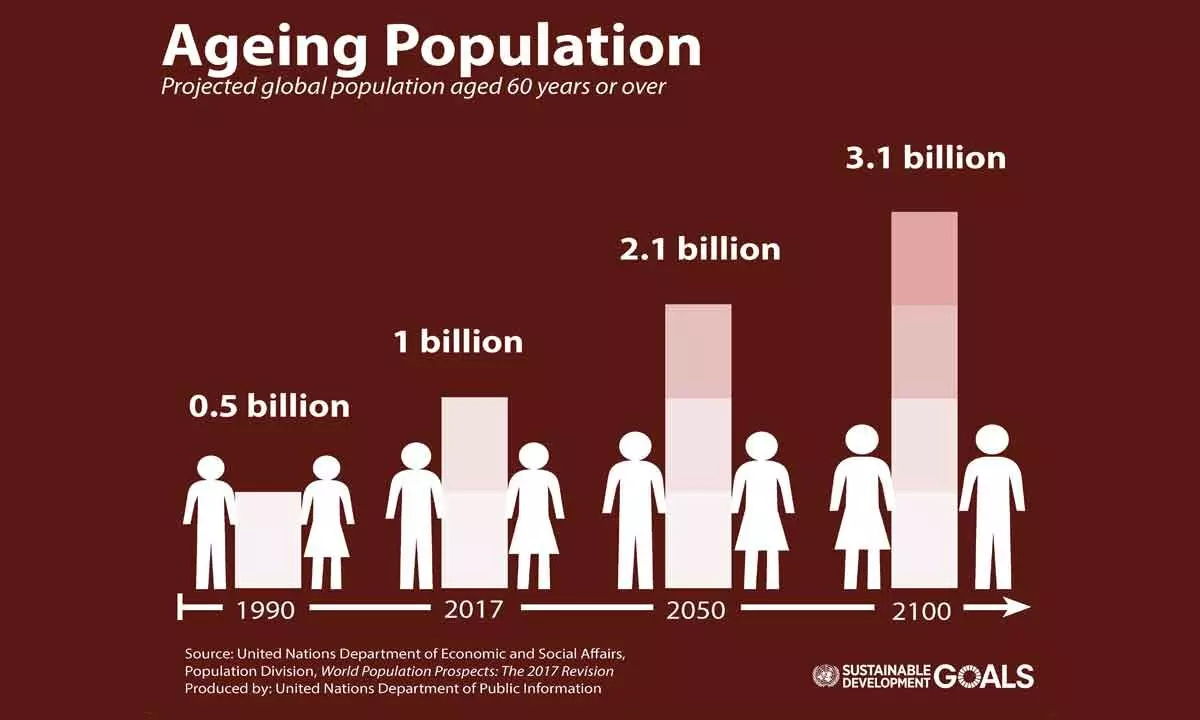

By 2030, one in 6 people in the world will be aged 60 years or over. By that time, their share of population will increase from one billion in 2020 to 1.4 billion and double by 2050 at approximately 2.1 billion. The number of persons aged 80 years or older is expected to triple between 2020 and 2050 to reach 426 million.

While this shift in distribution of a country's population towards older ages – known as population ageing – started in high-income countries (for example in Japan 30% of the population is already over 60 years old), it is now low- and middle-income countries that are experiencing the greatest change. By 2050, two-thirds of the world’s population over 60 years will live in low- and middle-income countries.

Evidence suggests that the proportion of life in good health has remained broadly constant, implying that the additional years are in poor health. If people can experience these extra years of life in good health and if they live in a supportive environment, their ability to do the things they value will be little different from that of a younger person. If these added years are dominated by declines in physical and mental capacity, the implications for older people and for society are more negative.

Although some of the variations in older people’s health are genetic, it is mostly due to people’s physical and social environments – including their homes, neighbourhoods and communities, as well as their personal characteristics – such as their sex, ethnicity and socioeconomic status. The environments that people live in as children – or even as developing fetuses – combined with their personal characteristics, have long-term effects on how they age.

There is no typical older person. Some 80-year-olds have physical and mental capacities similar to 30-year-olds. Other people experience significant declines in capacities at much younger ages. A comprehensive public health response must address this wide range of older people’s experiences and needs.

The diversity seen in older age is not random. A large part arises from people’s physical and social environments and the impact of these environments on their opportunities and health behaviour. The relationship we have with our environments is skewed by personal characteristics such as the family we were born into, our sex and our ethnicity, leading to inequalities in health.

Older people are often assumed to be frail or dependent and a burden to the society. Public health professionals, and society as a whole, need to address these and other ageist attitudes, which can lead to discrimination, affect the way policies are developed and the opportunities older people have to experience healthy aging.

Globalization, technological developments (transport and communication), urbanization, migration and changing gender norms are influencing the lives of older people, both directly and indirectly. A public health response must take stock of these current and projected trends and frame policies accordingly.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development sets out a universal plan of action to achieve sustainable development in a balanced manner and seeks to realize the human rights of all people. It calls for leaving no one behind and to ensure that the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are met for all segments of society, at all ages, with a particular focus on the most vulnerable—including older persons.

Therefore, while it is essential to address the exclusion and vulnerability of—and intersectional discrimination against—many older persons in the implementation of the new agenda, it is even more important to go beyond treating older persons as a vulnerable group. Older persons must be recognized as the active agents of societal development in order to achieve truly transformative, inclusive and sustainable development outcomes.

Countries could adopt policies to counteract the expected decline in the labour force. For example, reforms should focus on closing gender gaps in labour force participation, as Italy and Spain have done.

The potential here is significant, as only 50 per cent of women participate in the labour force globally, compared with 80 per cent of men. Promoting access to high-quality, affordable childcare could support an increase in young mothers in the labour market. Since labour force participation rates tend to decline for age groups closer to retirement, countries could adopt policies that encourage older workers to keep working, especially given the increase in longevity. Governments could make this easier by reconsidering taxes and benefits that favour early retirement.