Lilly's Alzheimer's drug isn't worth $20 billion yet

Alzheimer’s disease is a grim reality for many people as they age, with one in 10 US seniors older than 65 diagnosed with some form of dementia related to the ailment, according to the Alzheimer’s Association

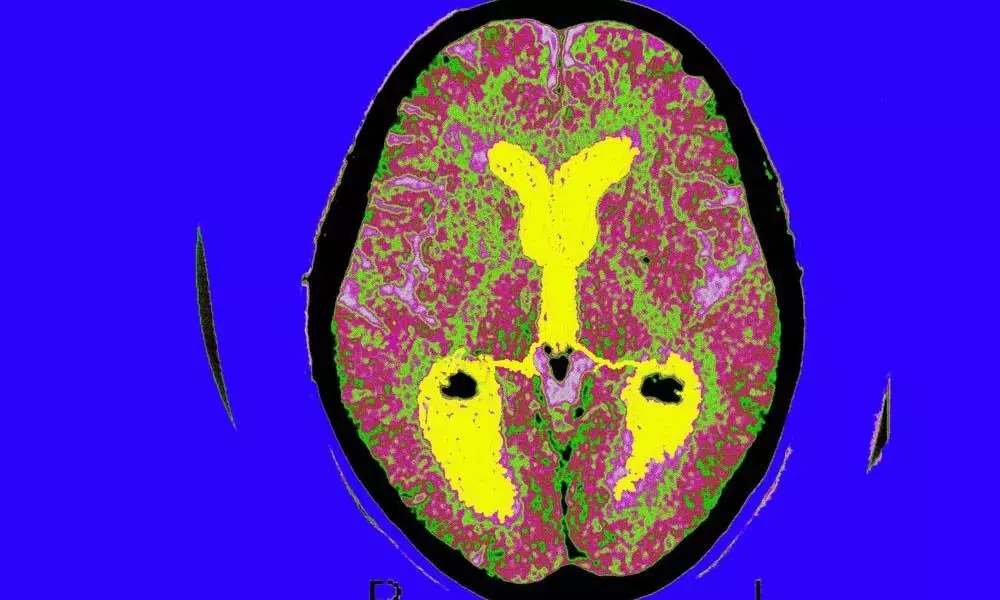

image for illustrative purpose

Alzheimer's disease is a grim reality for many people as they age, with one in 10 US seniors older than 65 diagnosed with some form of dementia related to the ailment, according to the Alzheimer's Association. Nothing on the market can effectively treat the disease, let alone halt its relentless progress, so a working therapy is akin to the holy grail for drugmakers and their investors.

Against this backdrop, Eli Lilly & Co. released data on Monday from a small Phase-II clinical trial for its antibody drug called donanemab, which showed significant slowing of decline for patients in early stages of the disease, compared with those who received a placebo. This was a surprise and investors cheered the news, sending Lilly's shares up more than 11 per cent and adding almost $20 billion to the company's market value. Shares of Biogen Inc., which is working on an Alzheimer's drug targeting similar problems in the brain as Lilly's treatment, also got a boost. Is this reaction justified? Sadly, as much as I would love to say yes, the answer is no, not yet. Here is why.

First, it's about how the trial was designed and what it was meant to show. Lilly's trial sought to gauge changes in both cognition and daily function of patients, which is different from other trials of Alzheimer's candidates, which sought to measure one or the other, or both but separately. That makes it hard to compare. And it's difficult to draw a firm conclusion about the results without more data that can help to explain any nuances related to this new measuring stick. The trial also missed some of its secondary goals, which included some of the more standard ways of measuring the efficacy of drugs for Alzheimer's.

Next, while the trial showed a slowing in decline by 32 per cent compared with a placebo over 76 weeks, it was set up under the assumption that it would show a 50 per cent reduction. As such, showing only 32 per cent may actually be viewed as a failure. This is an early trial with a new drug mechanism in a disease that is poorly understood, so we should be more forgiving. But even so, and more important, it's not clear that reducing the decline by a third is really meaningful in the long-term evolution of the disease. We simply need more detailed data.msg msg fazeli.

As for there being any connection to Biogen's Alzheimer's drug, called aducanumab, that's also tenuous. While the Lilly drug targets a similar enemy in the brain, namely amyloid and amyloid plaques, there are subtle but important differences in what type of amyloid it attacks. So there is no direct connection. Everyone wants to get a drug that can help us manage this awful disease, but it's still too soon to celebrate. We need more data and better trials to prove they are worth the clinical and financial risks. (Bloomberg)