Take cue from cotton farmers in two Haryana villages to avoid getting trapped in Chakravyuah

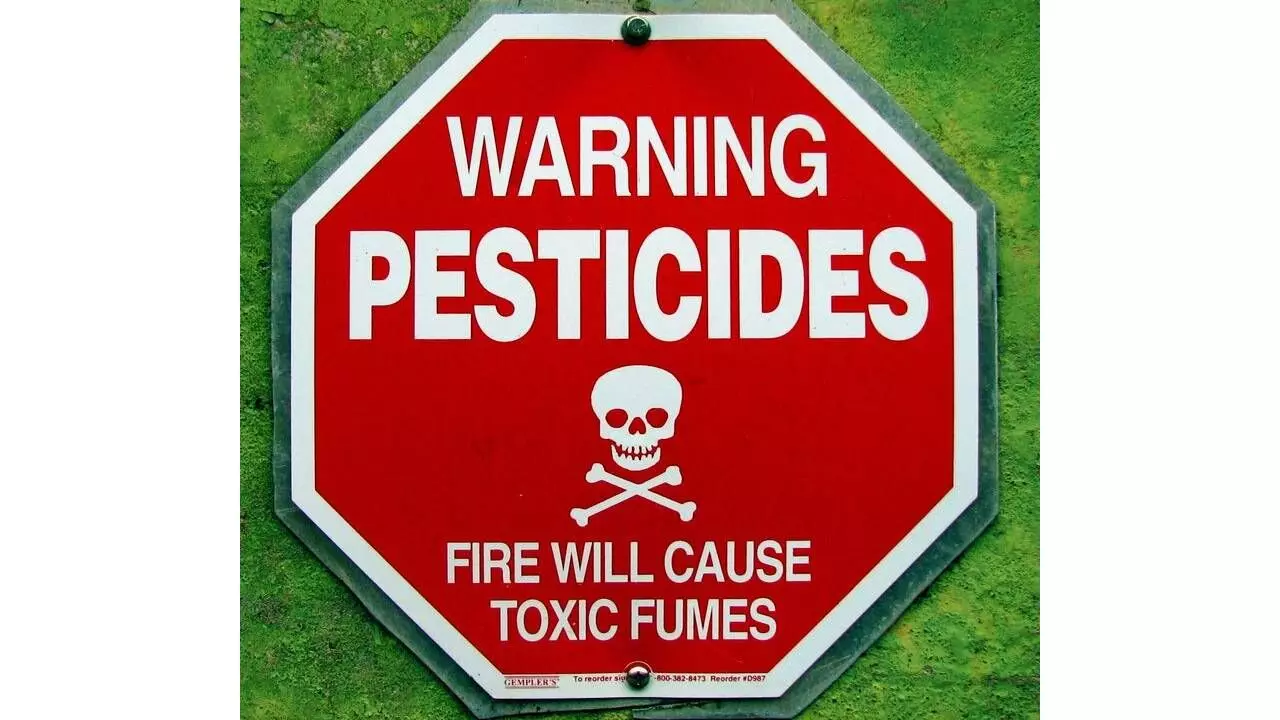

Cotton, as a crop, has more or less kept the pesticides industry alive

At the international level, I confronted a strong GM lobby, which wouldn’t even allow peer-reviewed scientific questioning of the GM research to come in the way. Sensible scientific voices were run down. Civil society, however, managed to hold on

When the Leader of Opposition in Lok Sabha Rahul Gandhi accused the ruling NDA Alliance of creating a Chakravyuah (vortex) to trap farmers, youth, MSME sector and the middle class, it reminded me of the times when I had often talked about another Chakravyuah that had trapped farmers in a vicious circle from which they have yet to get freedom.

It was in 2005 that I used the term Chakravyuah in an article that described the pesticides spiral that had gripped the farming community. Later, when genetically modified (GM) crops were introduced – and after Bt cotton was commercialised – I once again explained how the vortex had further tightened its grip.

In an article entitled: ‘Farmers are being pushed deeper and deeper into a death trap’ (Nov 17, 2015), I explained how the seven rings of Chakravyuah have been thrown around the farmers neck over the years, using cotton as an illustration, to drive home the point.

This is what I wrote: “Cotton farmers have been systematically pushed deeper and deeper over the years into a Chakravyuah from which the farmer is finding it difficult to come out. The more the attack of dreaded insect pests, the more is the use and abuse of chemical pesticides throwing a series of rings around the farmer. It has now been replaced with Bt cotton, which not only tightens the noose but also adds to more application of chemical pesticides thereby worsening the crisis.”

To explain, let’s go back to the times when India had emerged from the throes of the Second World War. After all, an alternate use for gases and chemical left behind had to be found out. These carryover stocks of harmful chemicals and gases began to be applied as pesticides. The first generation pesticides like DDT therefore found application on cotton pests. After a few years, the insects became resistant to these chemicals. Normally, the lesson here should have been to discard chemical sprays and look for alternatives, which included biological control. But with industry push, and with academia supporting the move, the effort switched to second generation pesticides.

After a few years, the insect again became resistant to the second generation pesticides. Again, a much safer and environmentally sustainable pathway of biological control was ignored. The reason was simple. Why would an industry let go of an opportunity to make money.

I have often said that cotton is a crop that has more or less kept the pesticides industry alive. There was a time when roughly 50 per cent of the total pesticides usage was on cotton alone. With cotton sustaining the industry to quite a large extent, it didn’t surely make any economic sense to kill the goose that laid golden eggs. Meanwhile, no wiser and saner voices within the agriculture system emerged to reduce independence on harmful chemicals. After a few years, as expected, the insect pests developed resistance also to these chemicals.

The third-generation pesticides soon gave way for the more potent and highly poisonous fourth generation chemicals. I remember when the fourth generation pesticides – called synthetic pyrethroids -- were introduced in the mid-1980s, several studies showed these chemicals to be very harmful, killing even birds and animals. But such was the vested interests that all these worries were set aside, and the universities began approving it one after another. I had raised alarm but as expected these were simply ignored. The argument given was that we need an immediate solution to protect the interests of the farming community which was suffering on account of the pest attack.

Nevertheless, the insect pest did get into control for a few years. Policy makers, top bureaucracy and agricultural scientists were visible happy. But after a few years, dreaded pests like bollworms remerged. This meant that the pest had become resistant to even synthetic pyrethroids, which were once considered to be the most harmful of the pesticides. Travelling in Punjab, some farmers had showed me how the pest would survive even when put in a bottle of the pesticide.

This was an era of chemical pesticides. When the scientific bandwagon shifted to genetically modified crop varieties of cotton, again agricultural scientists led the campaign. The argument then was that since the GM varieties have the ability to make a toxin within the plant, the use of chemical pesticides sprayed on the plant would slowly disappear. At the international level, I confronted a strong GM lobby, which wouldn’t even allow peer-reviewed scientific questioning of the GM research to come in the way. Sensible scientific voices were run down. Civil society, however, managed to hold on.

Anyway, returning to the cotton story, it is now evident that the claims of pesticides reduction with Bt cotton cultivation (which had a gene inserted from a soil microbe), turned out to be merely green-washing. After the single gene Bt cotton, the two-gene Bollgard-II was ushered in. And again, as it happened with different generations of chemical pesticides, the insect too had become resistant to these GM variants. While so much heat and dust was generated over the introduction of GM cotton varieties, the fact remains that keeping pace with times pesticide consumption too has increased.

Meanwhile, the call is now to get approval for Bt-III. In the Northwestern regions, where the area under cotton has slumped – from 10.23-lakh hectares last year to 6-lakh hectares this year – no lessons have been learnt. The Punjab government shockingly is asking for Bt-III varieties to tide over the crisis. In fact, the noose is further tightening around farmer’s neck.

If reports are to be believed, GMO-Free USA says pesticides industry is now getting ready with designer pesticides which can ‘edit’ genes in organisms.

And finally, the bigger question that needs to be asked is whether there is a way to get out of this Chakravyuah? Yes, as I said in my 2015 article, and I repeat again. A much safer and a healthy option exist – healthy for people, healthy for environment, and healthy for farmers. What should come as surprise is that there are villages which did not use any chemical pesticides to control cotton pests and yet have faced no pest outbreak.

“Farmers in Nidana and Lalit Khera, two tiny and non-descript villages in Jind district of Haryana, do not spray any chemical pesticides for several years now and have instead been using benign insects to control harmful pests. These 18 villages stand like an oasis in the polluted pesticides environment all around. Its time farmers too learn to make an effort to get out of the chakravyuah death trap.” Similarly, there are many ecological solutions that many cotton farmers have perfected in several parts of the country. It is therefore time for agricultural scientists and policy makers to get off the pesticides bandwagon, and learn from these farmers.

Let us make a concerted effort to free farmers from this deadly Chakravyuah.

(The author is a noted food policy analyst and an expert on issues related to the agriculture sector. He writes on food, agriculture and hunger)