No Conclusive Proof About Effects Of Artificial Sweeteners On One’s Health

We are hardwired to seek out high-sugar food for a source of energy to ensure our survival

No Conclusive Proof About Effects Of Artificial Sweeteners On One’s Health

The results indicate that artificial sweeteners may be making us more likely to form fat in our body – regardless of what we're consuming alongside the artificial sweeteners

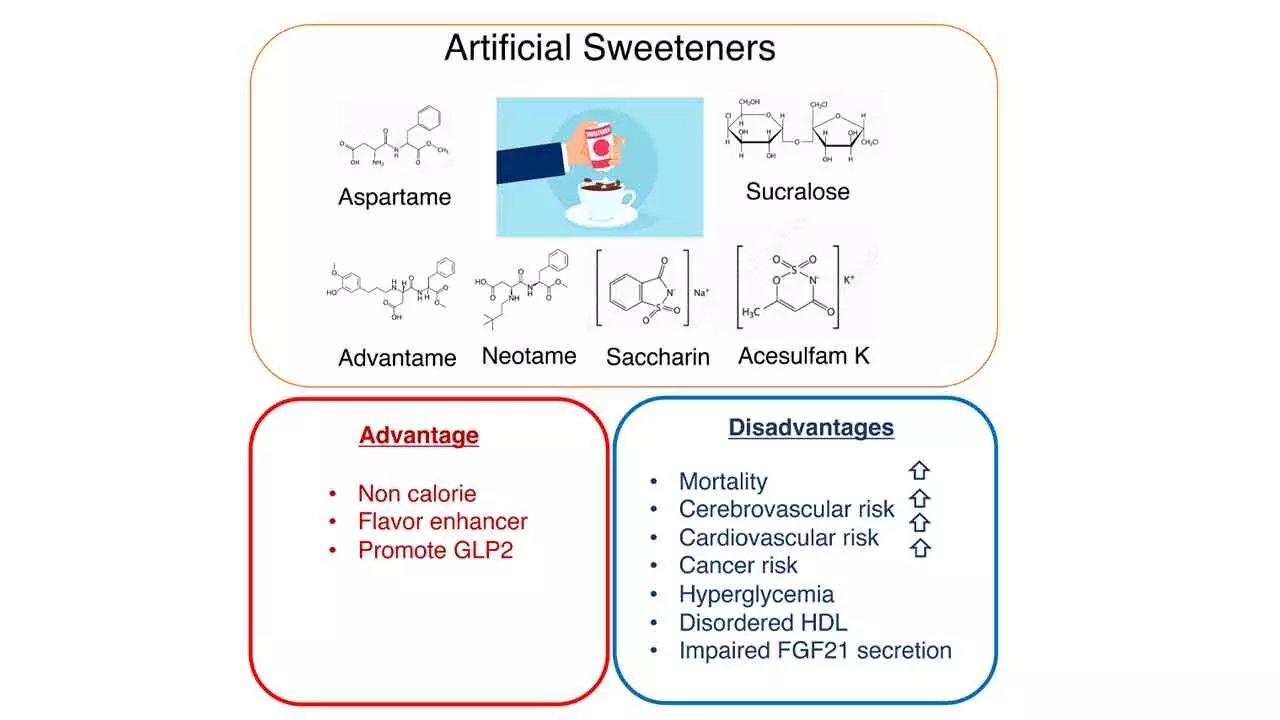

Artificial sweeteners are being added to a growing number of foods to reduce their sugar content while maintaining their appealing taste. But a growing body of research suggests these non-nutritive sweeteners may not always be a healthier and safer option.

So, what is our best option if we want to enjoy sweet-tasting foods without the harm of eating sugar? Artificial sweeteners were originally developed as chemicals to stimulate our sweet-taste sensing pathway. Like sugar molecules, these sweeteners act directly on our taste sensors in the mouth. They do this by sending a nerve signal to the body that a high-carbohydrate food source has been consumed – telling the body to break it down to use for energy.

In the case of sugar consumption, this also stimulates our dopaminergic system. This is the part of the brain responsible for motivation and reward, linked to sugar cravings. From an evolutionary perspective, this means we're hardwired to seek out high-sugar food for a source of energy and to ensure our survival. However, excessive consumption of sugar is well known to lead to health problems, such as metabolic disruption which can cause obesity and diabetes. Similarly, when artificial sweeteners, rather than sugar, cause this stimulation, there's increasing evidence of similar metabolic imbalances. This happens even though artificial sweeteners do not seem to stimulate the dopamine system. Indeed, a study published earlier this year showed that within two hours of consuming sucralose (an amount equivalent to the sugar in two cans of soft drink), participants exhibited increased physiological hunger responses.

Studies have also shown that sweeteners can stimulate the same neurons as the appetite hormone, leptin. Over time, this could cause our hunger threshold to increase – meaning we need to eat more food to feel full. This suggests that consuming artificial sweeteners makes us hungrier, which could ultimately make us consume more calories. But it doesn't stop at feeling hungrier.

A large study, which was conducted over 20 years, found a link between sweetener consumption and greater accumulation of body fat. Interestingly, the study found that people who regularly consumed large amounts of sweeteners (equivalent to three or four cans of diet soda per day) had a nearly 70 per cent greater incidence of obesity compared to those who consumed minimal amounts of artificial sweeteners (equivalent to half a can of diet soda per day).

The results indicate that artificial sweeteners may be making us more likely to form fat in our body – regardless of what we're consuming alongside the artificial sweeteners. A study published earlier this month also found that daily consumption of artificially sweetened drinks positively correlated with the incidence of type 2 diabetes. But given these drinks contain a range of additives – including acidifiers, dyes, emulsifiers and sweeteners – it's uncertain if this link can be entirely attributed to artificial sweeteners.

What you need to know:

So is it time to give up sweeteners completely? Maybe not! There are many studies that are adding to the controversy by showing that short-term substitution of sugar with artificial sweeteners reduces body weight and body fat. Numerous studies have also shown that artificial sweetener consumption has no association with the development of diabetes or even with indicators of diabetes, such as fasting glucose or insulin levels.

To address this, earlier this month, the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN), which advises the UK government on nutrition, released a position statement on the use of non-sugar sweeteners. This was in response to the World Health Organisation (WHO), which suggested that sweeteners shouldn't be used as a means of weight control due to their low-level association with the risk of developing obesity and type 2 diabetes. The SACN similarly concluded that non-sugar sweetener intake be minimised, especially for children. But they also stated that intake of sugars in general needs to be reduced. This is really at the heart of the issue. Artificial sweeteners may have significant negative health impacts, but are they as bad for us as sugar?

The overwhelming literature on the negatives of excess sugar consumption currently suggests no – but our understanding of artificial sweeteners is still not as extensive as that for sugar. We need more research on artificial sweeteners to better understand their effects.

Work is currently underway to collate a database of all clinical trials investigating sweetener use. This will allow us to better understand the sweetener research landscape and highlight areas where more work is needed. Until then, what should we do if we have a sweet tooth? Unfortunately, like everything with nutrition, it's best to only consume artificial sweeteners in moderation.

But one of the guidelines from the recent SACN review is that the industry clearly labels the number of artificial sweeteners in food and drink. So hopefully it will be easier for us to make these choices in the future.

(The writers are from Anglia Ruskin University)