Why water won't make it as a major commodity

The commodities that are most important to financial markets have several common characteristics: They’re used globally but produced at only a few locations

image for illustrative purpose

The world will benefit from putting a price on water

There's no commodity more central to human activity than the one that makes up 60 per cent of our bodies. So why isn't water a fixture of financial markets the way gold, crude, copper and soybeans are?

Some investors think it should be. It's the only asset that Michael Burry, the hedge fund manager played by Christian Bale in "The Big Short," still focuses on, if you believe the film's rather dubious closing sequence. CME Group Inc. is thinking along the same lines, launching futures contracts this week linked to California's $1.1 billion water market.

It's tempting to believe such a move could make H2O a commodity as central to financial markets as oil, metal and agricultural products - but don't hold your breath. The world will benefit from putting a price on water rather than treating it as a public good that's handed out for free, especially as climate change wreaks havoc with supply systems built for the 20th century. That doesn't mean that you'll ever see the price of Chicago water futures quoted on the evening news.

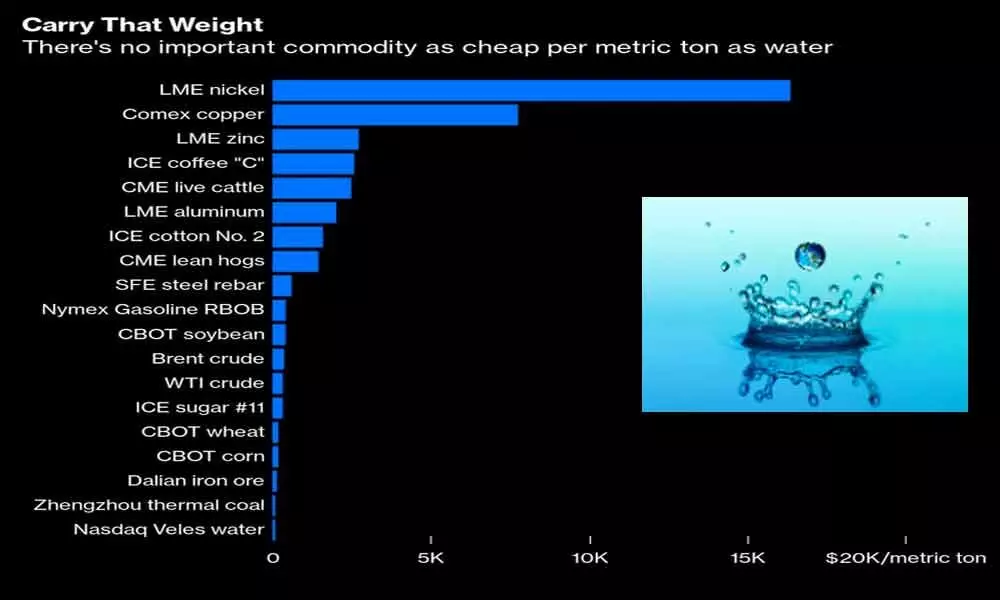

The reason ultimately comes down to abundance, price and weight. The commodities that are most important to financial markets have several common characteristics: They're used globally but produced at only a few locations; they're relatively scarce, and thus command a steep price; and their value is high relative to their mass, so that even at long distances the cost of freight is a small proportion of the ultimate price.

Take a look at the Nasdaq Veles Water Index, the base for CME's new water futures contract. An acre-foot of water currently costs $486.53, equivalent to 39 cents per metric ton. A ton of gold, on the other hand, changes hands for an almighty $60 million. Copper traded on Comex costs $7,706; Brent crude goes for $355; and at the lower end, even coal at Australia's Newcastle port will set you back $77.35.

Those differentials determine the viability of global trade in commodities. Precious metals are so expensive that they're typically transported by air, a fact that caused havoc in the gold market earlier this year when the Covid pandemic grounded much of the world's aviation fleet. Almost everything else moves more cheaply on boats, trains and trucks, with the cost of transport taking up a rising share of final prices as the value per ton goes down. It typically costs between $5 and $10 a ton to ship coal from Australia's east coast to consumers in northeast Asia, making long-distance trade just about viable. There's little point, however, in spending dollars transporting water that changes hands in its end-markets for mere cents.

That's particularly the case because, for all we talk about water scarcity, it's hugely abundant compared to any other commodity. In most places it can be collected for free by just attaching a tank to your drainpipe. Even in places with low rainfall, desalination is a far cheaper option than long-distance transport.

As a result, there's never going to be a global market for water - and that means it's never going to fly as a major commodity. Taking a derivatives position in LME copper is a reasonable way for a Chinese electronics company to hedge its raw-materials price risk. Any time the physical price of copper in China gets too out of line with financial futures in London, traders will move in to take advantage of the differential by shipping metal from one place to the other. The same can't be said with water.

We see something comparable in the power market, which is also highly localized. Electricity revenues in Germany come to roughly 80 billion euros ($96.9 billion) a year, but the value of all contracts outstanding for the main baseload power derivative is a mere 698 million euros, because only generators and major consumers in Germany have any interest in the market. In the US, power trading is even more marginal: Off-peak electricity open interest in the PJM West market, the most-held contract, comes to just $383,000. Turning such quasi-public goods into commodities has a justly bad reputation in the U.S., after Enron Corp.'s attempts to manipulate the California power market in 2001 caused rolling blackouts and ultimately contributed to the company's collapse.

Still, even if water never becomes a global benchmark, the motivation for a futures market is a sensible one. The recent success of Europe's carbon markets after years of glut is evidence that once the institutional settings are put right, a price on low-value public resources is crucial to encouraging less profligate use. Everywhere on the planet that water is being misused, it's being overused. (Bloomberg)

David Fickling