India-Pakistan trade ties turn sour

The ban was imposed when India altered the constitutional status of Jammu & Kashmir

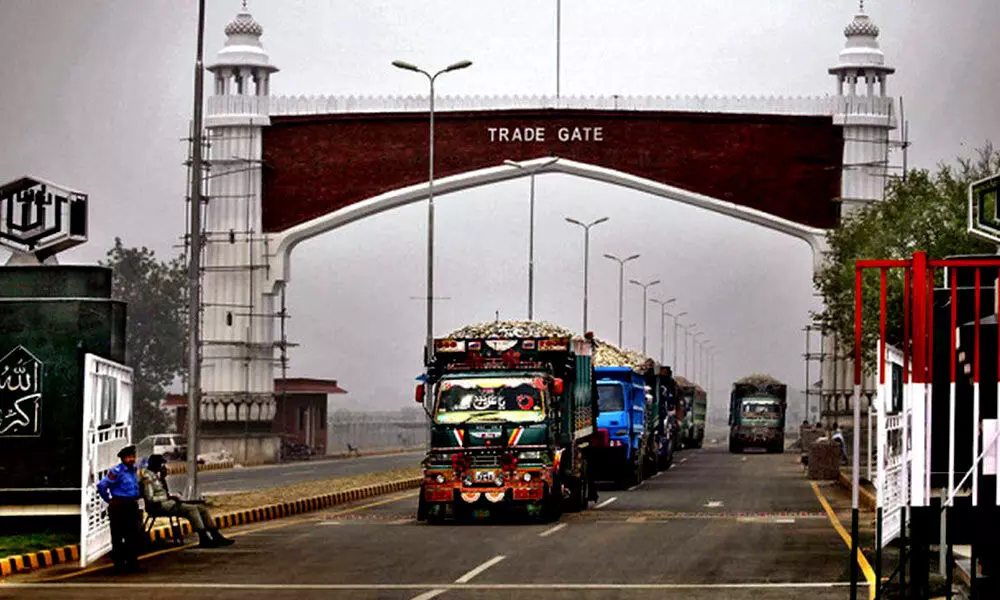

image for illustrative purpose

Pakistan's sudden decision to resume trade with India and equally quick reversal after 24 hours has put the spotlight on economic ties between the two countries. If trade had resumed after a gap of 19 months, it would have been a significant development in the bilateral relationship even if the value of transactions was not large. The earlier plan was to lift the ban on trade with India for only two commodities, sugar and cotton. But it was expected that the list of tradable goods would have been expanded gradually.

The ban was imposed when India altered the constitutional status of Jammu & Kashmir. And it is on these grounds that the revised decision was articulated by the Human Rights Minister, who said trade could only be resumed after India restores the earlier status of Kashmir. But trade flows had already received a big blow prior to the ban by Pakistan when India decided to withdraw the grant of Most Favoured Nation status to its western neighbour after the Pulwama attack. It had simultaneously decided to impose 200 per cent duty on all imports from the neighbouring country. This immediately resulted in imports falling to negligible levels of about 14 million dollars in 2019-20 while exports fell by over 60 per cent to about 815 million dollars.

It must be recalled that before withdrawal of MFN status, trade between the two countries was estimated at 2.6 billion dollars in 2018-19, of which as much as 2 billion dollars was in the form of exports to Pakistan. As for MFN status, it comes under the rules of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) which mandates that members must provide non-discriminatory access to other member countries. India had granted this status to Pakistan as long ago as 1996, but there had been no reciprocal concession by that country. When India withdrew such status, it invoked the WTO provision allowing for exceptions on security grounds.

When the ban on trade was imposed by Pakistan, most exports to that country were diverted via Dubai. In fact, even in normal times, a large amount of trade between the two countries goes through this informal route rather than via the Wagah-Attari border. Rough estimates are that the value of India-Pakistan informal trade going through either Dubai or Singapore could have been as high 5 to 10 billion dollars even earlier.

One of the reasons for the circuitous route is that Pakistan had maintained a negative list of about 1200 items that could not be imported from India. These are the items that are sent through this informal trade channel.

Through the official route, however, Pakistan was largely importing cotton and organic chemicals prior to the ban. Other major imports were plastic goods, tanning and dyeing extracts and machinery. India, on the other hand, had been buying mineral oils, edible fruits and nuts, salt, ores and raw hides and leather from that country.

The decision and the reversal on the trade issue have taken place after the Line of Control ceasefire announced by the two countries in February. Now that the trade ban continues to remain in place, it clear that any wider economic cooperation between the two countries will have to be part of a larger dialogue process. There is no doubt, however, that trade and economic collaboration will be beneficial to both sides in the long run. It was short-sighted on the part of Pakistan earlier to have denied the MFN status to India when this country had done so without any hesitation. And despite worsening of ties over the years, India did not withdraw this concession even though there was no reciprocity. Ultimately, it was only after the Pulwama attack that a harder line was taken by the Modi government on economic and trade ties. Even then, however, there was no ban imposed on bilateral trade and it was left to Pakistan to snap this critical relationship about 19 months ago.

The widening of economic and trade ties between countries of South Asia had been the major impetus for the formation of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC). It was envisaged that in the long run, despite political differences, countries in the region could get a boost to their economies by promoting free trade in the region. Other parts of the world, notably Europe and East Asia have benefited greatly from their regional economic groupings like the European Union and ASEAN. But SAARC has not been able to live up to its initial potential largely because of strife between India and Pakistan. Even though it would be in both countries self-interest to have collaboration in areas such as power generation, oil and gas pipeline networks as well as enhancing trade, any initiatives in this direction have failed due to cross-border terrorism issues.

Although the resumption of trade and that too in only two commodities would have been a tenuous beginning, it could conceivably have led to greater economic cooperation between the two countries. The scenario has now moved back two steps. The freeze in bilateral economic ties now looks set to continue for a longer period unless the backchannel talks that are reported to be under way yield some concrete results.