EU bans 10 banks from bond sales over anti-trust breaches

By barring JPMorgan Chase & Co., Citigroup Inc., NatWest Group Plc, Bank of America Corp., Barclays Plc and others, it has excluded many of the largest players in European debt markets

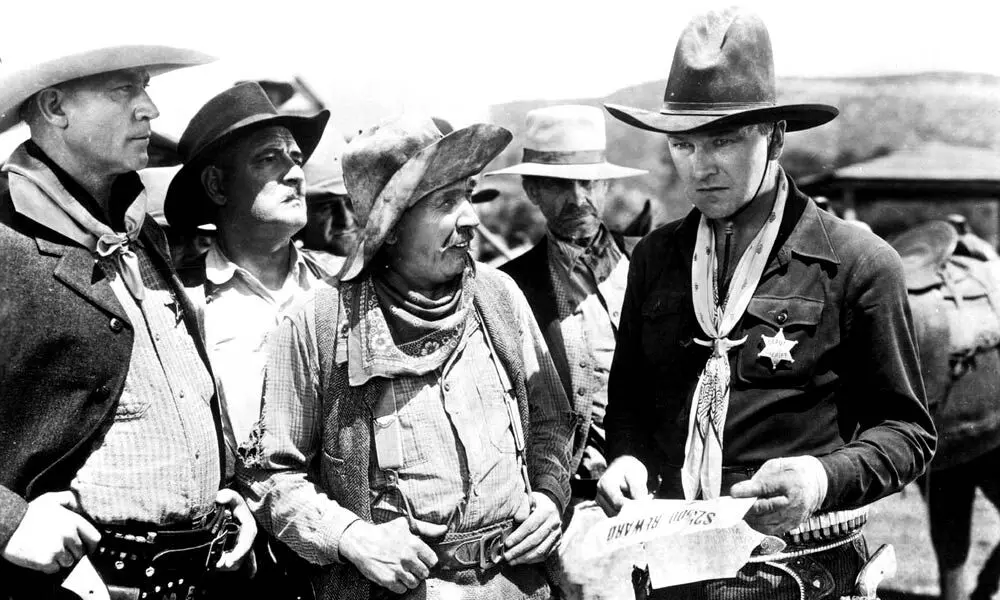

image for illustrative purpose

The European Commission has just sent the clearest signal possible to global investment banks that there will be zero tolerance of market rigging in the bloc's financial markets. By excluding 10 large banks from the syndicate for Tuesday's blowout 20 billion-euro ($24 billion) bond sale for the EU's pandemic recovery fund, Brussels has introduced a new and painful form of punishment for traders who have ever shared sensitive pricing information with their counterparts at other firms

There's a new sheriff in town for financial markets. The European Commission, the administrative center of the EU, has just sent the clearest signal possible to global investment banks that there will be zero tolerance of market rigging in the bloc's financial markets.

By excluding 10 large banks from the syndicate for Tuesday's blowout 20 billion-euro ($24 billion) bond sale for the EU's pandemic recovery fund, Brussels has introduced a new and painful form of punishment for traders who have ever shared sensitive pricing information with their counterparts at other firms.

The Commission says the freeze will remain while it assesses previous breaches of antitrust rules. So instead of being allowed to move on after a fine or a rap on the knuckles for collusion, the message has gone out that there will be consequences for future involvement in EU financing, too.

With the Commission emerging as a bond-issuing colossus as it raises the money for its 800 billion-euro ($970 billion) NextGenerationEU fund, it has newfound clout against previous market miscreants, and fully intends to use it. By barring JPMorgan Chase & Co., Citigroup Inc., NatWest Group Plc, Bank of America Corp., Barclays Plc and others, it has excluded many of the largest players in European debt markets.

It's a punchy move as some bankers will question whether it's fair to introduce a new sanction years after the misdeeds took place - and after previous punishments. It's also a bold step for Brussels to assume a semi-regulatory stance, when the European Central Bank is the official supervisor for the euro area's banking system, and national regulators also play a key role. Some might construe this as overreach.

And while Brussels is in the happy position of experiencing huge appetite for its paper right now, if there were a dip in demand it might have to rely on a reduced pool of syndicated banks in the global bond markets. (In a syndicated bond sale, a group of banks is paid to drum up demand from investors.)

Still, the excluded banks will be stinging. First there's the reputational hit of not being considered worthy of the biggest-ticket bond sale in EU capital markets. Then there's the question of whether other European sovereign issuers will feel that they have to follow suit in targeting ex-offenders. It's possible that the ban could widen across public entities - and could take in lucrative business such as derivative swap hedging.

This is reminiscent of Citi's ban from conducting capital markets business for Italy in 2004. To get back into the EU's good books, the banks will have to show that they've taken remedial measures to prevent future antitrust breaches. It's not clear how this will work, and how objective the EU will be in making its decisions. Might it favour banks from within the bloc?

The banned banks won't be excluded from the separate primary dealer system for the NextGen fund, which will start in September and will feature regular government bond-style auctions and liquidity taps. Nonetheless, that's less rewarding than the 17.5 basis points of fees available in Tuesday's sale.

If this turns out to be a temporary measure and the reinstatement process is open and fair then perhaps this could be the kick the banking industry needs to demonstrate a permanent change in its market integrity. But this could have been part of a coordinated and well-communicated response from the regulator, not just what looks like a random act from a suddenly powerful issuer. (Bloomberg)